More than 300 operating mines plumb the Arizona desert landscape, most of them quarrying sand and crushed rock for industrial and commercial use — a $450 million takeaway in 2017.

Mining is part of Arizona's economic and cultural heritage dating back hundreds of years to when Native Americans plinked for turquoise and coal. Spanish explorers invaded the region in the 1600s looking for silver and gold to carry back across the Atlantic. Today, more than 300 operating mines plumb the Arizona desert landscape, most of them quarrying sand and crushed rock for industrial and commercial use — a $450 million takeaway in 2017.

And then there's copper. The reddish-brown mineral isn't as ubiquitous as aggregate, but historic and operating copper mines dot a wide swath of the state running from Bisbee near the Mexican border 300 miles northwest to Jerome, which overlooks the Verde Valley in the Black Hills. Current mines are mostly clustered in the southeast quadrant of the state east of Phoenix and Tucson — and a brand-new mine is about to join them.

In-Situ Mine

In the fall of 2017, the state issued an operating permit for what will be Arizona's first new copper mine in more than a decade. Vancouver-based Excelsior Mining was given permission to start developing a 9,500-acre property southeast of Tucson near Benson and Wilcox in Cochise County. As the year ended, all that remained after issuance of the state permit was a federal EPA go-ahead. Excelsior executives were not available for interviews for this article.

Some $47 million in initial construction costs will be invested by Excelsior to set up a mine that is expected to produce copper for a quarter century. But it won't look like mining to casual observers. The operation eschews traditional mining methods as imagined in popular lore. Hard-hatted miners won't trudge into a tunnel in the side of a mountain with pickaxes resting on their shoulders. Excelsior's Gunnison Copper Project will extract copper by employing in-situ leaching.

The method involves drilling down into a copper deposit, which may have been explosively fractured for easier access. A leaching solution is pumped down the hole and dissolves the ore. The resulting solution is pumped to the surface, where the copper is extracted and processed. If all goes as planned, the mine will be brought online in stages with eventual full production of 125 million lbs. of copper cathode per year.

The project is appealing to state officials because it is environmentally friendly—nearly all the water pumped into the ground is recovered and reused — and because it will infuse Arizona's economy with some $3 billion over the life of the mine. This low-profile copper recovery operation is quite different from the common image many people have in their minds when they think of copper mines — vast open pits.

Open Pit Mining

Just 90 mi. north of Wilcox is a prime example of such an operation: the Morenci mine. Owned jointly by Freeport-McMoRan and Japan's Sumitomo Metal Mining, the Morenci operation began nearly 150 years ago as an underground undertaking and has evolved into a whole complex of surface-mining activities. Together, they constitute one of the largest open-pit mining operations in the world. The mine employs some 3,300 people and, in 2017, produced 740 million lbs. of copper. McMoRan executives declined to be interviewed.

As is typical of open-pit mining, the Morenci operation has miles of benches circling each gigantic excavation. The benching allows the holes to be stair-stepped into the ground one level at a time. An upward sloping haul road is carved from the hillside for ore-bearing trucks to carry 400-ton payloads of ore to a processor at ground level. The Morenci mine has reportedly produced as much as 900,000 metric tons of ore in a day. The mine also is the home of the world's first commercial copper concentrate leaching-electrowinning process, which integrates sulphide treatment with other processing methods.

As is typical of open-pit mining, the Morenci operation has miles of benches circling each gigantic excavation. The benching allows the holes to be stair-stepped into the ground one level at a time. An upward sloping haul road is carved from the hillside for ore-bearing trucks to carry 400-ton payloads of ore to a processor at ground level. The Morenci mine has reportedly produced as much as 900,000 metric tons of ore in a day. The mine also is the home of the world's first commercial copper concentrate leaching-electrowinning process, which integrates sulphide treatment with other processing methods.

Such a massive open-air operation has environmental implications, of course, beginning with the excavation itself. Some open-pit mines have displaced so much earth that they are plainly identifiable by orbiting astronauts. Restoring such manmade holes in the ground to a more natural and sustainable condition comes at an enormous cost, which is factored into every open-pit operating and reclamation budget.

Furthermore, severe ecological impact can result from the disruption of the natural balance of water and ground cover, exacerbated by piles of accumulated waste. Widespread erosion and air and water pollution can result from all this. For example, in 2012, the Morenci operation was fined several million dollars by the U.S. Department of the Interior for air pollution violations.

However, the fact of the matter is, no matter how one goes about it, extracting copper ore from Mother Earth is a dirty job, an earth-shattering job. Nature is natural, a manmade excavation obviously is not. Consequently, every proposed mine anywhere is opposed by naturalists and other communities wanting to leave acreage undisturbed, even if that means leaving valuable minerals in the ground for perpetuity. In Arizona, mining opposition includes Native American populations.

Deep Mining

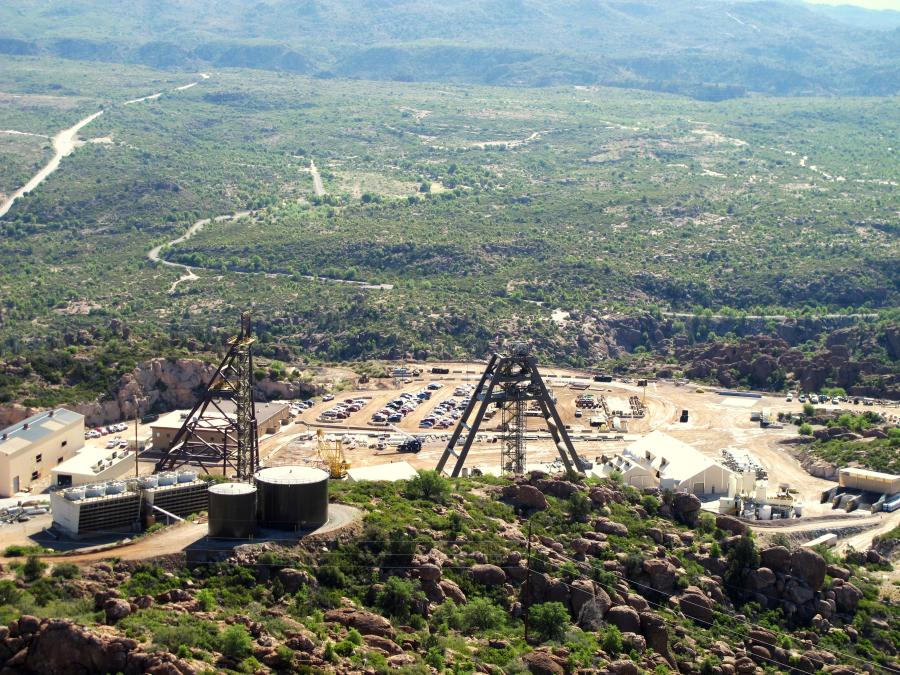

Near Superior, Ariz., two of the world's largest mining companies — Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton — are developing a copper mine that is notable for its depth and for early opposition from Native American communities. Dubbed the Resolution Copper Mine, its shafts dive into the earth for more than a mile and will have laterals running between them under the copper deposit. In essence, the ore is mined from beneath, a method called block cave mining.

Why would Indian tribes or any other community find such deep-down activity undesirable? Out of sight, out of mind. Yet the mined ore ultimately is moved to the surface for processing, and tailings from processes will be mounded on site. Furthermore, the removal of ore deep within the earth eventually leads to the sinking of the surface area above it. The Resolution mine depression ultimately could be a mile or so across and as deep as a thousand feet.

This eventual deformation of the land, which sits on the edge of Tonto National Forest, was protested by San Carlos Apache leaders, the Sierra Club, and other environmental groups. The Apaches were concerned about water pollution. They also feared damage to sacred sites such as a cliff area called Apache Leap, even though the Resolution mining operations are 20 mi. from the San Carlos Apache Nation boundaries and outside of any areas considered sacred. For their part, environmentalists saw threats to recreational areas.

A struggle to win approval of the mine went on for a full decade. Finally, in 2014, Congress approved a federal land swap that allowed the project to begin. To develop the mine on their 2,400 acres, the two international mining companies bought up and exchanged 5,300 acres of prime recreational, conservation and culturally significant land elsewhere in the state. In addition, near Apache Leap — where 75 trapped Apaches warriors are said to have leapt to their deaths rather than surrender to U.S. Cavalry soldiers — 142 acres were donated by Resolution Copper Mine to the U.S. Forest Service as a part of an 839-acre special management area in which mining will be barred.

In the four years since the agreement finally was reached, Resolution Copper company officials have continued to meet with area residents in Superior, where the company is headquartered. The “community working group” meets in the Superior Chamber of Commerce office and includes leaders from towns situated across the local area and San Carlos Apache representatives. Topics range from social and environmental impact issues to air quality, health standards and recreational changes.

“We've been working with the community and Native Americans for many years now, collaborating, having dialogue, listening and providing input,” said Kyle Bennett, principal advisor of communications at Rio Tinto Kennecott in Utah. Kennecott is a subsidiary of Rio Tinto.

“In January, the U.S. Forest Service finalized a plan after a consultation process with 12 tribes and, in addition, the Town of Superior. We are starting to see all the stakeholders coming together in a cooperative way to help shape the project.”

According to Resolution Copper spokesman Jonathan Ward, an Arizona State University survey shows some lingering opposition to the project, but 85 percent of the local community now approves of it. Maintaining such support is important because the mine is still a decade away from beginning production.

Currently, the mine's engineers are both digging and data collecting. The digging is happening in No. 9 shaft, a vertical excavation that drops 4,800 ft. A concrete tube, 21 ft. in diameter, is being constructed inside it. The shaft was created in 1971 for a previous mining operation on the site and now is being rehabilitated and deepened to 6,800 ft., a process that will take two more years.

Currently, the mine's engineers are both digging and data collecting. The digging is happening in No. 9 shaft, a vertical excavation that drops 4,800 ft. A concrete tube, 21 ft. in diameter, is being constructed inside it. The shaft was created in 1971 for a previous mining operation on the site and now is being rehabilitated and deepened to 6,800 ft., a process that will take two more years.

At the bottom of the shaft, a lateral tunnel will be excavated that will connect to shaft No. 10. That shaft — which required removal of 475,000 tons of rock — is an all-new penetration of the site. Its tube is 28 ft. in diameter and bottoms out almost 7,000 ft. below the surface. The two shafts skirt the edge of what is expected to become North America's biggest copper mine, with some two billion metric tons of copper-bearing ore awaiting recovery. Over the 40-year life of the mine, additional shafts will be sunk alongside the deposit.

Because air pressure and geothermal factors raise temperatures so far underground — to well above 120 degrees Fahrenheit in some cases — fans and refrigerator units are being installed at various depths to pump cooling air into the tunnels as well as into deep-underground computer work stations and offices adjacent to the shaft. (The heat is, of course, not a local phenomenon. Some South African mines are almost 2.5 mi. deep and have bottom temperatures in the range of 140 degrees Fahrenheit.)

Topside, ongoing work at Resolution includes reclamation activity stemming from the site's old Magma Mine. This year, some 125 Resolution employees are working above and below ground. At full production, after the shafts are functioning and the processing and transportation facilities are built, the mine will have a workforce of 1,400 people.

Pre-production investments for deep mining are as massive as the operation itself. Some $600 million is being expended just to sink and prepare the two shafts. In all, $7 billion is expected to be spent by the partnering companies before the first copper ore is raised to the surface. Analysts for London-based Rio Tinto, which owns 55 percent of the project, are betting the price of the commodity will stay high enough over the long haul to recoup all that expense and then some.

During the last decade, the price of a pound of copper has ranged from $2 up to $4. As of mid-April, it stood at $3.13. What must the price average in the years ahead for the mine to be profitable? Bennett, the Rio Tinto Kennecott spokesman from Utah, would only say it all depends.

“You have to measure that on a case-by-case basis. A lot of factors come into play, including development costs and production,” he said. “I would say in general we invest in long-life, low-cost assets. We feel that geologically this is going to be one of the greatest copper assets in the world once we have a chance to actually mine it.”

Which is good news for Arizona.

As Bennett puts it, Resolution Copper Mine will provide “a significant financial contribution to the state of Arizona and local economies. The economic piece of the operation is very strong.”

Specifically, the mine is expected to produce about $1 billion in economic benefits for Arizona every year, or more than $60 billion by the time the huge copper deposit a mile down is depleted.

CEG

Mining Engineer Goes Deep to Study Arizona From Below

Mining Engineer Goes Deep to Study Arizona From Below

Kim Huether is into rock. Deep into it.

The Rio Tinto mining engineer is responsible for leading technical studies of the Resolution Copper Mine project near Superior, Ariz. Specifically, she is studying southeast Arizona geology more than a mile below the surface of the mine's entrance where a massive deposit of copper-bearing ore awaits recovery.

That sounds like pretty interesting stuff to those of us whose day consists of pushing paper at a desk or sitting in commuter traffic twice a day. Huether said she also finds it interesting, even though she has been at it for 20 years. “It is still exciting. Every mine has its own appeal.”

Huether has been on the Resolution Copper Mine site for 14 months, but it isn't her first deep-mine experience. A graduate of South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, she has studied deep-underground mines — as well as other types of ore-recovery operations — for company properties elsewhere in the United States as well as in Australia, Indonesia and Mongolia.

This one in Arizona is a different professional experience because the mine is still being developed.

“I actually have quite a passion for this project,” she said. “It is challenging and exciting to be in on it this early. A lot of the other operations in which I was involved were already operating and I was only trying to make them better.”

She was asked if the Resolution Copper Mine is technically challenging in any way.

“They all seem challenging,” she said. “I think the most challenging thing about it is the depth. We are down 7,000 ft. and with that comes some really significant challenges, geotechnical challenges, like how the rock is going to behave at that depth.”

She hopes to stay with the Resolution project for the next couple of stages of development and perhaps longer and watch a mine move almost from inception to production. For now, she is settling in for a few years of data-gathering. Drilling information. Extensive monitoring of underground conditions. Environmental studies. To a commuting paper-pusher, that all sounds a trifle boring. Not to an engineer, however.

“It is quite interesting, actually,” Huether said.

For a woman to be in this critical management position on a project of this scope is somewhat notable, but Huether said she is not breaking a glass ceiling or anything.

“There are quite a few of us [women] out there in these positions and have been for quite a while. We are very lucky.”

Today's top stories

As is typical of open-pit mining, the Morenci operation has miles of benches circling each gigantic excavation. The benching allows the holes to be stair-stepped into the ground one level at a time. An upward sloping haul road is carved from the hillside for ore-bearing trucks to carry 400-ton payloads of ore to a processor at ground level. The Morenci mine has reportedly produced as much as 900,000 metric tons of ore in a day. The mine also is the home of the world's first commercial copper concentrate leaching-electrowinning process, which integrates sulphide treatment with other processing methods.

As is typical of open-pit mining, the Morenci operation has miles of benches circling each gigantic excavation. The benching allows the holes to be stair-stepped into the ground one level at a time. An upward sloping haul road is carved from the hillside for ore-bearing trucks to carry 400-ton payloads of ore to a processor at ground level. The Morenci mine has reportedly produced as much as 900,000 metric tons of ore in a day. The mine also is the home of the world's first commercial copper concentrate leaching-electrowinning process, which integrates sulphide treatment with other processing methods. Currently, the mine's engineers are both digging and data collecting. The digging is happening in No. 9 shaft, a vertical excavation that drops 4,800 ft. A concrete tube, 21 ft. in diameter, is being constructed inside it. The shaft was created in 1971 for a previous mining operation on the site and now is being rehabilitated and deepened to 6,800 ft., a process that will take two more years.

Currently, the mine's engineers are both digging and data collecting. The digging is happening in No. 9 shaft, a vertical excavation that drops 4,800 ft. A concrete tube, 21 ft. in diameter, is being constructed inside it. The shaft was created in 1971 for a previous mining operation on the site and now is being rehabilitated and deepened to 6,800 ft., a process that will take two more years. Mining Engineer Goes Deep to Study Arizona From Below

Mining Engineer Goes Deep to Study Arizona From Below