The LeeBoy sons, (L-R) Tommy (son-in-law), Keith (son), Mike (son) and Eric (son). All work in LeeBoy research and development.

This is the story about the building of an iconic American brand. A tale of a farm boy who uses his ingenuity, grit and entrepreneurial spirit to build a company that created an industry. It's something straight out of Norman Rockwell's sketchbook. But the story of the LeeBoy brand, its patriarch and the family behind him, is not confined to the past; the company and its brand are stronger today than ever. In the company's 55-year history are lessons of survival that hundreds of family-owned small businesses in the commercial paving industry can relate to.

Lesson 1: What's Your Vision?

B.R. Lee.

At its core, the story of LeeBoy is about culture — of a time, of a place and of a man; and how that culture drove the development of a successful company, enabling it to make the transition from a family-owned mom-and-pop operation to a corporation that dominates the domestic commercial paving market. Of course, Billy Robert (B.R.) Lee wasn't thinking about any of that when he got out of the Army in 1962. He was 29 and wondering how he was going to support a young growing family in rural North Carolina.

"In the army, Dad ran a motorgrader. When he got out, he did grading for the ballfields around Charlotte before he and his brothers started a small commercial paving business," said Mike Lee, the eldest of B.R. and Nelda Lee's four children and still a LeeBoy employee.

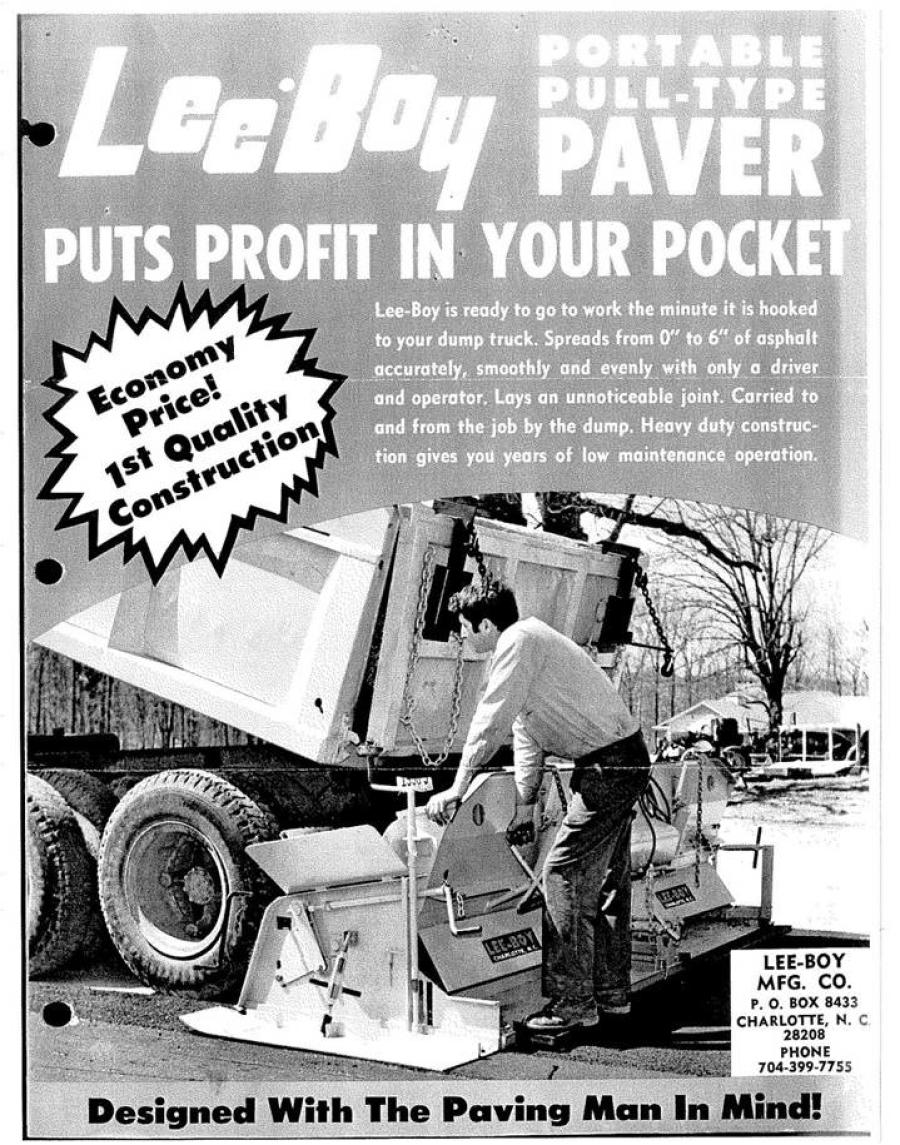

Using shovels and lutes to spread truckloads of hot mix was backbreaking, dirty work that paid little. A drag box paver would have been a huge help but was financially out of reach for the Lee boys. (Yes, that's how the company eventually got its name.) So B.R. did what came naturally, he built his own.

"Momma and Daddy's first house was modest. He built a garage on the side of it and that's where he built his first pull-box paver," said Mike. But to say he built those early machines entirely by himself wouldn't be accurate. Oftentimes his wife Nelda served as his right hand, literally.

"She would hold the steel in place while he welded," Mike said. "Every time he'd finish a couple of pavers, he'd load them up on a trailer hitched to his 1959 Cadillac and hit the road. He wouldn't come home until he sold them all."

Eventually the pull boxes started selling and B.R. began thinking beyond pavers. He realized that the rural paving contractor in the ‘60s had little or no upward mobility. Working by hand severely limited their productivity, effectively capping their income. If he could help increase their productivity, these struggling family-owned enterprises may be able to grow and thrive.

In 1970, B.R. announced to his brothers that he was going to manufacture the first self-propelled paver that the average commercial contractor could afford. His brothers tried to dissuade B.R., arguing that the pull boxes he was making were selling, but he held firm.

"If he'd stuck with the pull boxes, we'd all be working for somebody else right now," Mike said with a laugh. B.R. and Nelda scraped together enough money to buy a small shop in Shuffletown, a tiny farming community northwest of Charlotte.

The first self-propelled commercial pavers were basic. Paving widths ranged from 8 to 12 feet. They had tilt hoppers, extendable screeds and cut-offs. The operator had a good view over the hopper. Those first machines sold for about $10,000. It took a while for the business to get going. Meanwhile, attempts were being made to reverse engineer B.R.'s design.

"There was this one guy, a paving contractor, who was good friends with my dad and actually operated one of his pull boxes. When Daddy was working on his first self-propelled design the guy attempted to replicate it. He wasn't interested in making pavers to sell, he just wanted one for himself. Eventually he got it running but couldn't duplicate the screed, so he bought one from Daddy and started paving around town with it," Mike said.

The exposure within the local paving community was enough to create interest. Most importantly, their interest reaffirmed what B.R. intuitively knew: an affordably priced, self-propelled commercial paver could be a game-changer for many small paving companies who were struggling.

Lesson 2: Take Care of Your People and Let Them Pay It Forward

Through the 1960s, LeeBoy was little more than a feel-good story about a successful start-up. Even with a successful first year under their belt, there was no guarantee B.R. and Nelda would make it to the second year.

What separates those who survive from those who don't? For one thing, survivors are able to build a strong team of individuals who are committed to the founder's vision and can instill it in others who come on board. In B.R.'s case, the management team consisted of his family.

"I started working in the business when I was 12. My job was to paint everything he made. I'd go to school during the day then come home and start painting and work into the night," said Mike. His younger siblings, Eric, Keith and Sissy have similar stories.

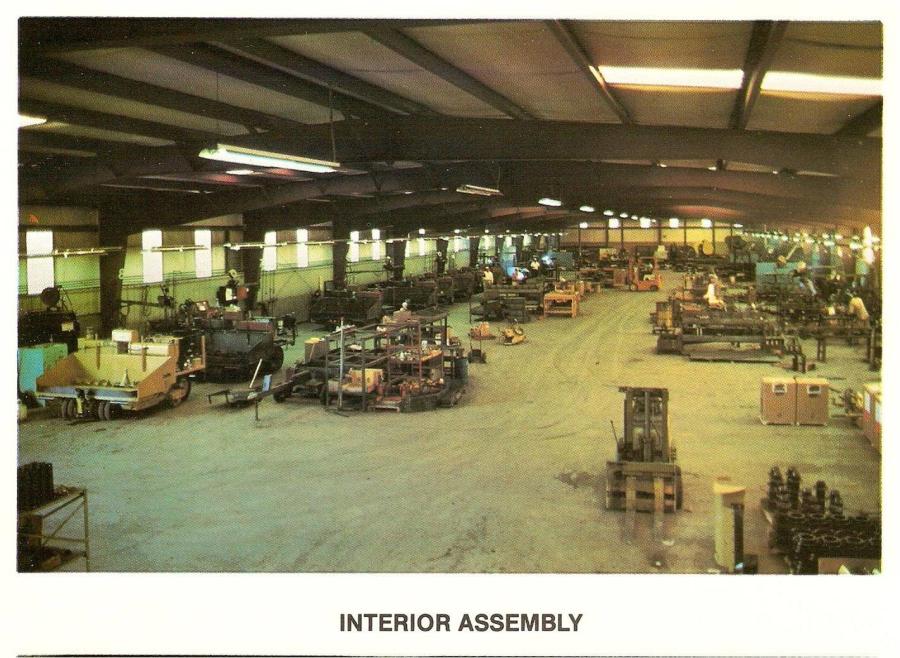

The old maintainer shop.

The work ethic B.R. and Nelda instilled in their children was passed along to the third generation. Brandon Weese, the oldest of B.R and Nelda's eight grandkids, remembers, "My parents [Tommy and Sissy] were in the shop six days a week. From age 10, so was I." He and cousin, Blake Lee, earned $3 an hour sweeping the shop. Over time, their responsibilities grew as they learned to weld and work on hydraulics and engines.

Today, LeeBoy's annual employee retention rate is well above the 70-percent national average for the manufacturing and distribution sector. Among the company's 300 employees, the average tenure is more than seven years, about 75-percent longer than the sector. Half the employees have been with the company longer than five years. Among that group, the average tenure jumps to 13 ½ years.

Much of the credit for the high employee retention numbers goes to the culture of empowerment and pay-for-performance instilled early on by B.R. Payment was based on production. The more pavers that went out the door, the more money everybody made. But there was no cutting corners. The company's relationships with its customers were sacred.

Lesson 3: Relationships Are Your Most Valuable Asset

Throughout the first half of the 1970s, the Lee family and a handful of non-family employees worked to improve and expand the company's product line and grow the dealer network. In the Charlotte area, the company sold direct to the small commercial paving contractors, which played to its strength. To reach other markets, the growing company established relationships with dealers, mainly in the southeast. As business grew, the dealer network expanded north and then west.

By the mid-70s revenues were over $1 million and the company had a small but loyal and growing network of dealers. Thinking he had accomplished his goal — to provide small contractors a path toward upward mobility and secure his family's financial future — B.R. sold the company in 1977 for just over $2 million. The new owner, Joe Jim Corp., was a bridge contractor based in Florida. They brought in a team of ex-military officers to run the business and things quickly began to unravel. Within a few months profits and productivity began to fall as product quality and service levels dropped — along with inventory levels.

"Turns out, folks were stealing individual parts and selling them off as unassembled machines. They had more stuff going out the back door than the front door," Mike said.

More important than the financial damage was the effect on the company's relationships with customers and dealers. That was more than B.R. could stomach. In 1979, he bought the company back for pennies on the dollar and set to work repairing the damaged relationships and restoring the company's (and his family's) reputation.

Over the next few years, the company succeeded in re-building the trust. More importantly, the value of that trust — built on quality manufacturing, service and integrity — was permanently seared into the corporate culture.

"That little episode made us realize that our most valuable assets are the relationships and trust we've built over time," said Brandon, who is now LeeBoy's production manager.

The Lee family, (L-R) Eric (son), Nelda (wife), Mike (son), Sissy (daughter), Keith (son) and B.R. Lee.

Throughout the 1980s, LeeBoy focused on expanding and improving its equipment portfolio. Significant changes included the 1985 introduction of the Series 1000 pavers, which relocated the engine from beneath the hopper to the rear of the machine. In 1988, they added motorgraders to the product offering.

By the 1990s, LeeBoy was still very much a family operation. B.R. was at the helm, Nelda ran payroll and the boys, including Sissy's husband, Tommy, all worked in production. It was a lean operation to say the least. As long as they could sketch out mechanical drawings on a sheet of paper — or with chalk on a concrete floor, as Brandon remembers — there was no need for technology.

Employees punched clocks and payroll checks were handwritten and recorded in a ledger book. Today, that mentality seems counter-intuitive as well as counter-productive, but it contributed significantly in cementing the independent can-do attitude that has become a hallmark of the LeeBoy brand.

Lesson 4: Know Your Limitations

By 2000, the company was producing about 15 different models of paving and road maintenance equipment and supporting dealers in all 50 U.S. states and 10 Canadian provinces. The business environment in which it was operating was quickly evolving as well. Across the U.S. industrial sector, technology was radically transforming how companies design, manufacture, sell and support their products.

"The way business was done was totally different from what my parents and grandparents were used to," said Brandon, the first in the family to attend college. By the time he graduated, B.R., then 67, was thinking it might be time to turn the business over to someone more capable of shepherding it into the new millennium.

He was determined not to make the same mistake twice. When he was approached by Crescent Capital, a holding company from Atlanta, Ga., he proceeded with caution. In January 2000, Crescent Capital and its co-investors acquired B.R. Lee.

After the company sold, B.R. stayed on as a consultant talking with customers. "He really missed that," Mike said.

B.R. passed away in 2003 at the age of 69.

"The day he died, he was tinkering around with the design of an electric pedal car for retirement communities," said Brandon. "He never stopped working."

In June 2006, VT Systems (Alexandria, Va.) via its parent company ST Engineering, purchased B.R. Lee Ind. from Crescent Capital. The move gave LeeBoy access to significantly more resources, access to cutting edge technologies and the necessary capital and business management experience to continue the company's growth. One of the first investments VT Systems made in LeeBoy was to slowly introduce technology to facilitate processes such as product design, inventory management and back office functions.

Today, LeeBoy employs more than 300 people. It is one of the top performing companies within the VT Systems family, which includes companies in the aerospace, land, electronics and marine industries.

Lesson 5: Refer Back to Lesson 1

The strength of the company's culture is proven by the fact it has transcended the founding family which, in many ways, is the litmus test for determining the long-term survivability of any small family-owned enterprise. Just a third of family-owned businesses pass control to the second generation and only 12 percent will see the third generation involved. Of the eight grandchildren, four are still with the company.

While LeeBoy is no longer a family-owned business, it does feel like one, and that, according to Christopher Barnard, LeeBoy's chief executive officer, is one of the hidden secrets to the company's long-term success and something that VT Systems found so attractive.

"I believe that from the beginning, ST Engineering through VT Systems recognized that the company and culture the Lee family had built was working really well," he said. "The challenge was how to modernize the business systems and operational processes without compromising the culture," he added.

Before joining the company, Barnard already had a deep respect for the unique characteristics common to many successful family-owned businesses. Prior to LeeBoy, Barnard served 18 years as president and chief executive officer of Wacker Neuson Corp. that through one of its original forming companies, Wacker Construction Equipment, traces its roots back to 1848.

He points to Germany's "Mittelstand" as one model for managing corporate culture in order to cultivate success. The term refers to the approximately 3.6 million small and medium sized businesses, many with original family-owned ownership, that power much of the German economy. As a group, these companies exhibit a unique set of characteristics, including:

- Family culture

- Generational continuity

- Long-term focus

- Independence

- Agility

- Loyal workforce

- Innovation

- Customer focus

The LeeBoy grandchildren, (L-R) Brandon Weese, production supervisor; Garrett Weese, quality control; Todd Jenkins, engineering; Shane Lee; Lindsay Lee, accounting; and Tamara Helderman, human resources.

Barnard sees all of these same ingredients at LeeBoy. The strategy over the next three to five years will be to build on the company's culture of grit and focus on the commercial paving contractor, while investing heavily in product and process innovation and investment in the critical and necessary dealer-customer relationship.

For now, the company will continue focusing on the North American, Central American and South American markets as it works to strengthen its brand overseas. In these markets for many years, LeeBoy has parlayed its relationships with customers, dealers and vendors into a dominant brand.

Another challenge is recognizing how quickly many areas of the business are evolving and being able to adapt while remaining true to the culture. The key is taking an inside out approach, starting with what you do best.

"For us that's building the best machines, finding the best dealers and, together, doing everything possible to help the paving contractor. This unique focus is why the LeeBoy brand is known in the marketplace with the unique tag line ‘Built with the paving professional in mind,'" Barnard said.

These non-negotiable requirements are the "what." The "how" are the processes and tools needed to keep pace with changes in technology, product designs, marketing, manufacturing processes, communication and more. It all begins and ends, however, with the employees who make it possible.

"B.R. had it right and you can't change that because that's the key to everything else," Barnard cautioned. LeeBoy will always stay true to its original core values that have driven and will continue to drive its success.

Today's top stories