Jack Nye at the shop November 2008.

Nye Manufacturing Ltd. builds heavy-duty construction and demolition attachments that are almost as tough as company founder Jack Nye. Extremely durable, innovative and precise — that describes both the man and the products of the Canadian manufacturing company he launched 68 years ago in Ontario.

The family-owned company still custom-builds each of its grapples, stump harvesters, pulverizers and other attachments because Jack Nye built them that way. Each piece is one of a kind, maybe not quite as individual as when the founder was turning them out, but nevertheless built according to each end-user's wishes.

When son Mark Nye succeeded his father as company president 20 years ago, he immediately took the entire line and "harmonized" the thickness of plates and other components of each attachment so the manufacturing process would be more repeatable. Jack's method had been to build the attachments sort of by instinct, tweaking them here and there as he went along.

"I went through the lineup and identified all the best things my father had done ad hoc," he said, standardizing design elements, incorporating the lessons that Jack Nye had learned and applied in subsequent renditions of a tool. "That's what I brought into the company. But sometimes it would annoy Dad when I did that. I'd reassure him that in every case I'd used his original design, which was a proven design, but that we still would make incremental improvements as needed. That probably was when we quit being a blacksmith shop and became a manufacturer."

Reassured or not, Jack Nye, who is 95, still comes into the plant each day to keep an eye on things.

***

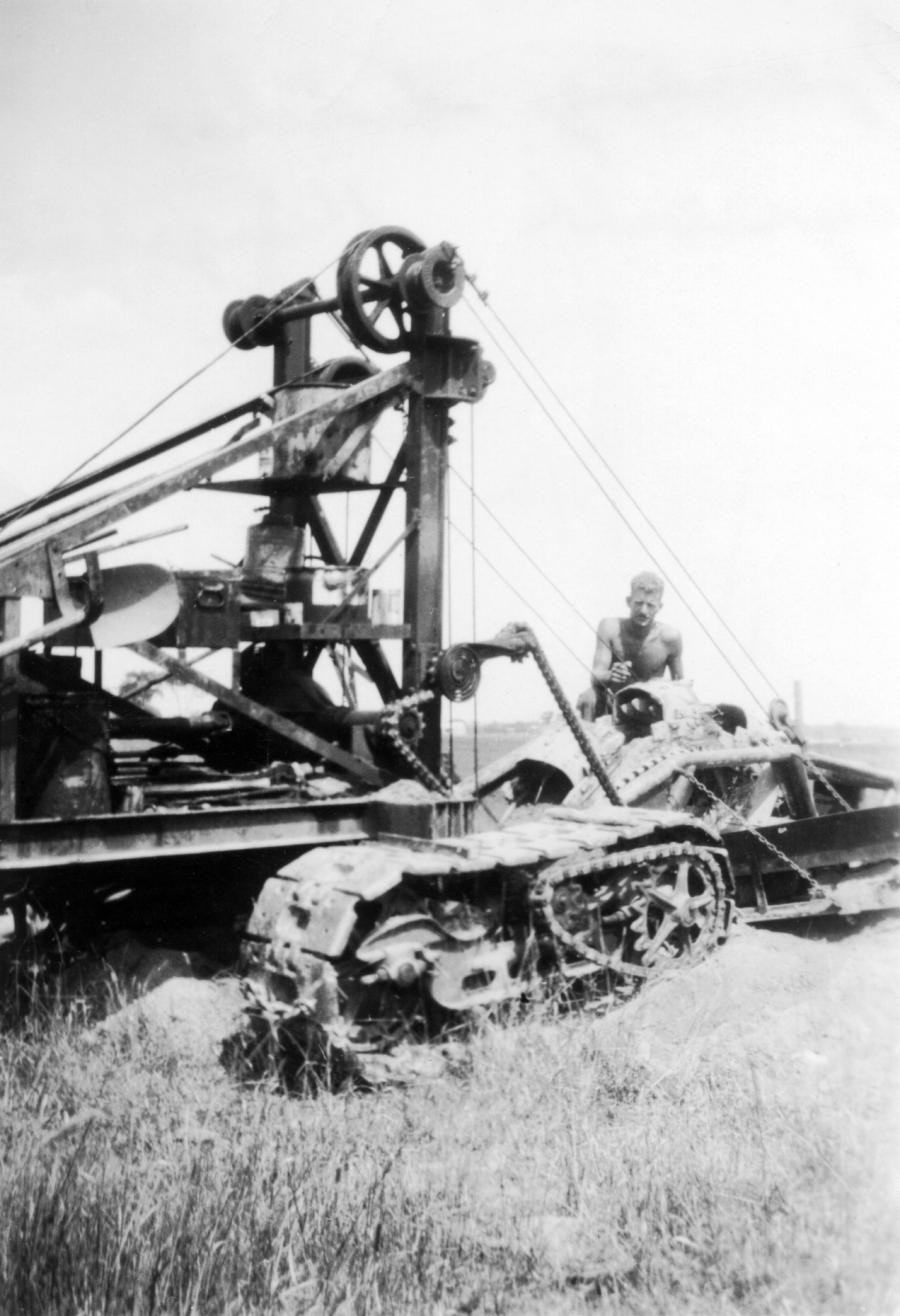

Blacksmithing indeed was the genesis of Nye manufacturing. Jack Nye grew up on a farm northeast of London, England. His father, Charles, was a farm manager and young Jack always was around horses and steam-powered tractors and engines.

He also had a proper English fascination with the sea. When he was 12 years old, he dragged a galvanized water trough for horses to a nearby stream and used it as a boat. "His father gave him a good beating for that," said Mark Nye. (The punishment clearly didn't stunt the boy's love of boating: Years later, he fabricated steel work boats for various Ontario marine contractors, none of the craft seagoing, and went on to make an estimated 19 crossings of the Atlantic Ocean, two of them solo.)

In 1938 at age 14, Jack completed a metal-working shop class and promptly dropped out of school. He enrolled in an ag technical school and learned blacksmithing. Within a year, he was welding steel and repairing agricultural equipment. A year after that, his world took a turn for the worse when the German threat to Europe and Great Britain loomed.

Jack, his older brother and father joined the Home Guard and trained as soldiers to help defend the island from invasion. After work, Jack would climb water towers to keep an eye out for Luftwaffe bombers, He taught some fellow Guardsmen how to weld. And as soon as the Royal Navy would accept him — he was just 17 when it did — he was assigned to the battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth. For the next three years, he and his shipmates plied the North Atlantic and then the Pacific Ocean as part of the Southeast Asia Command.

Aboard ship, Jack continued to hone his metal-working skills, working as a stoker but also laboring in the industrial shop shaping and drilling steel and producing technical drawings. Even so, the war was crashing all around him and the teenager survived some harrowing moments.

In one instance during fighting near Burma (now called Myanmar), he was assigned to crawl in the ship's propeller shaft tunnel, with the door latched behind him, to monitor oil and water cooling requirements for the 36-inch-diameter revolving shaft.

"The ship would shudder and lurch during the fighting," Mark Nye said of his father's recollections, "and he didn't know if the battleship had been hit or what. He began to imagine being locked in the shaft room with the ship sinking. It was very hard on him."

Jack's father and brother both fought on European soil. By war's end, all the family members were able to return home unharmed and Jack married Rosalind Harradine, who also had served in the war as a WREN (Women's Royal Navy Service).

***

The couple settled into a rural area south of London, with Jack blacksmithing and fabricating metal pieces for local farmers. In those post-war days, supplies such as tanks of acetylene and oxygen were hard to come by because of government restrictions. The couple chafed at the red tape. Three years of frustration led to a decision to emigrate to Canada.

"Actually, Dad applied to move to South Africa, but his application was denied for some reason … not enough education or finances or something. Thank God for that," Mark Nye said. "Their second choice was Canada."

Jack Nye did pass muster with Canadian immigration authorities, who also had restrictions on immigrants to ensure they could support themselves.

Unable to find metal work right away, however, Jack Nye took a job installing drainage pipe in a field, a process involving a bucket-wheel trencher. What happened next speaks to the confidence of a young man who started work at 15 and fought in a world war as a teenager.

"One day the company boss came by and noticed that Jack was working by himself," recounted Mark Nye "The job foreman wasn't there. The boss asked where the foreman was. Dad said, ‘I let him go.' The boss just looked at Dad and asked, ‘You let the foreman go?' Dad said, "Ah, he was being a bit of a twit, but everything is going just fine without him, as you can see.' So Dad was made foreman. He was pretty scrappy."

The senior Nye did land some welding work, including for Horton Steel, where he volunteered to work high up in a water tower being built at the jet engine plant for the Avro Arrow. Why opt for the high-up risky work? It earned him danger pay. Finally, he decided it was time to start working for himself. He cut a couple of round holes in the trunk lid of a Pontiac for acetylene and oxygen bottles, added a 200-amp welding unit and launched a mobile welding service. Rosalind Nye kept the books.

In 1952, Nye Welding moved into its first shop, which was home for the company until 1970 when it was moved to its current location on Mavis Road. Hydraulic excavators had begun to have a large presence in Canada by then and contractors regularly approached Jack about fabricating sturdier, more effective buckets and other attachments.

"Dad was never the type to say no, so before long he was building excavator buckets," Mark Nye said.

Specialized attachments like tilt buckets and rippers soon followed and the Nye name began to be associated exclusively with attachments, mostly for excavators. Demolition tools followed in the 1980s. Mark Nye talked about what distinguished those early Nye products from that of the competition.

"Virtually from the start of our efforts in manufacturing demolition attachments, we used the finest steel available and typically used thicker steel than what was used by most of our competitors," he said. "Every piece is welded using low hydrogen weld flux core wire. This is a smoky process and a difficult process, but it also creates the strongest weld possible. It's one of the reasons why our demolition attachments have a reputation for being nearly indestructible."

In 1992, Nye was contacted by Scott Guimond of a U.S. distribution firm, National Attachments. After getting to know Guimond, Nye agreed to let National distribute Nye attachments in the eastern U.S. The Canadian company's mechanical grapplers and concrete pulverizers quickly found customers south of the border. The alliance continues, with National now distributing across the United States.

"In the last year, we expanded our product offering with what I believe is the best engineered and strongest stump harvester on the market anywhere in the world," said Mark Nye. "National Attachments has done a great job launching that product in the U.S. market."

Sales of Nye products are approaching 50-50 distribution between the Canadian and U.S. markets and the company has no interest in pursuing markets outside North America.

***

In 2020, Nye Manufacturing has what Mark Nye believes is the widest range of attachments in the industry. Its most popular tools are mechanical concrete pulverizers, stump harvesters, demolition grapples and various types of stick extensions, along with especially heavy-duty buckets. The company's attachments average three or four tons in weight, with the largest being a 15-ton bucket for iron ore operations.

The tools still are individually fabricated for customers and are, of course, built from computer-aided designs. Nye jokef that he didn't really introduce CAD to the company's manufacturing process. His father did.

"My father's system was cardboard-assisted design. He would create full-sized cardboard templates of buckets. He spent hours creating thousands of templates. He just loved the idea of having a template in his hands."

A signature product of the company's was a so-called digital pulverizer with an integrated ripper. It was introduced in the 1990s when the word "digital" was de rigueur. "It had a ripping digit, a ripper shank, so I used digital as a play on words."

The same playfulness is evident in the company's website content. On the site are found such phrases as T-Rex pulverizer, a Rhino horn "to rip, flip and back-drag," lower and upper "fangs" and tools "chomping through stumps." Nye owns up to creating the phraseology, but his interest is more than just word deep. He is a fan of biomimetics, or the imitation of biological features in machine engineering.

"When you're sitting in a comfortable, air-conditioned office, eating Cheezies and working on your computer, there's no excuse for a crappy design," Nye said. "Some manufacturers will cut out some triangle shapes for gripping points on an attachment, but that's not the way a tooth looks. A tooth is curved back toward the jaw joint. The front of the tooth is concave to make clearance for material to flow. We don't produce any dumb triangles and corners without a nice radius. We're after the most efficient and effective designs."

This mimicking of nature is evident in the company's GSX garbage shear used to reduce the size of solid waste in trucks and landfills. The teeth on the shear are modeled on those of a tropical or subtropical wahoo fish.

"We went deep-sea fishing in the Bahamas and I caught a wahoo about three feet long," Nye said. "I looked at its teeth and they're not normal. They bypass one another like a serrated tin snip. The teeth can cut through about anything you put in there."

He took photos and replicated the jaw action on the GSX.

His bio-mimicking extends to the painting of all teeth on an attachment white, though the rest of the tool is painted whatever color a customer wants to match his machine.

"Painting the teeth white is such a pain in the ass," he admitted, though it does produce some striking-looking attachments.

***

Mark Nye looks back on his father's career and attributes its success to Jack Nye's iron will and tenacity.

"It required hard work and technical sense to do what he did and he wasn't afraid to take on new challenges. He almost willed things to be the way he wanted them."

Mark Nye calls welding "a beautiful thing. You can see what needs to be done and visualize how it will look when completed."

He added that the elder Nye's work was never artwork as such.

"What he made always had utility. Some of it was ornamental iron work, but it always was practical. Wrought-iron door knockers. Railings. Fireplace irons. He built an ornamental lamp at the end of our driveway."

Mark Nye's two sons, Michael and Bradley, are third-generation family members in the company and are working their way into leadership positions as mechanical and technology engineers. On Fridays, the brothers regularly join their father and grandfather for lunch somewhere. Might a larger manufacturer come into the picture someday and disrupt this family scene?

"The company is not for sale," the president said. "It is a legacy of my father that I've built upon, doing all I could to honor the family name. My kids are on the road to doing the same thing. I'm proud of the business and of the Nye name and I wouldn't want it any other way." CEG

Today's top stories