Once those are in place, DEP will shut down the Delaware Aqueduct to connect the bypass tunnel to the existing aqueduct.

(New York City DEP photo)

Considered the largest and most complex repair project in the 176-year history of New York City's drinking water supply, a $1 billion effort is under way to repair two areas of leakage within the 85-mile Delaware Aqueduct. The primary leak will be eliminated through construction of a 2.5-mi. bypass tunnel, being drilled below the Hudson River from Newburgh to Wappinger.

"This project is a big deal for New York City, because it involves fixing our largest aqueduct, which happens to be the longest tunnel in the world," said Adam Bosch, director of public affairs, New York City Environmental Protection, Bureau of Water Supply. "Because the tunnel is leaking about 18 to 20 million gallons of water each day into the Hudson River, we knew it had to be fixed sooner, rather than later. But a number of things had to come together first."

The Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), which employs scientists, engineers, surveyors, watershed maintainers and other professionals, manages New York City's water supply, providing more than 1 billion gal. of water each day to more than 9.5 million users. This includes more than 70 upstate communities and institutions in Ulster, Orange, Putnam and Westchester counties, who consume an average of 110 million gal. of drinking water daily from the water supply system. This water comes from watersheds extending more than 125 mi. from the city, with the system comprising 19 reservoirs, three controlled lakes and numerous tunnels and aqueducts.

"New York City's water comes from three reservoir systems — the Croton, Catskill and Delaware. When this leak was first discovered about 1990, there was not sufficient capacity in the other two systems, Croton and Catskill, to sustain the city during a shutdown of the Delaware Aqueduct. Since then, the city has implemented a number of programs including advanced metering in our distribution system, toilet replacements, etc., to drive down the consumption of water in the five boroughs."

"New York City's water comes from three reservoir systems — the Croton, Catskill and Delaware. When this leak was first discovered about 1990, there was not sufficient capacity in the other two systems, Croton and Catskill, to sustain the city during a shutdown of the Delaware Aqueduct. Since then, the city has implemented a number of programs including advanced metering in our distribution system, toilet replacements, etc., to drive down the consumption of water in the five boroughs."

According to Bosch, the effort has been extremely effective.

"Since 1990, the city has grown by about 1.5 million people, but its water consumption has dropped by approximately 35 percent. With water consumption now down around one billion gallons per day, we do have enough transmission capacity in our other two aqueducts for the Delaware Aqueduct to be shut down and repaired. The Delaware Aqueduct will be shut down in 2022 to 2023 for about six months to connect the bypass tunnel to structurally sound portions of the existing aqueduct."

Bosch said it's rewarding to see progress being made on a daily basis.

"It's incredibly gratifying to see the work started, progressing well and moving toward completion in 2023. For many of our workers, the assessment, monitoring and repair of the leak will span their entire career. That's how big and complex a project it is. What's more, the bypass tunnel was designed internally by DEP. We are one of the few, if not the only, government agency that has retained the internal capacity to design tunnels, so our tunnel designers are particularly proud of this project."

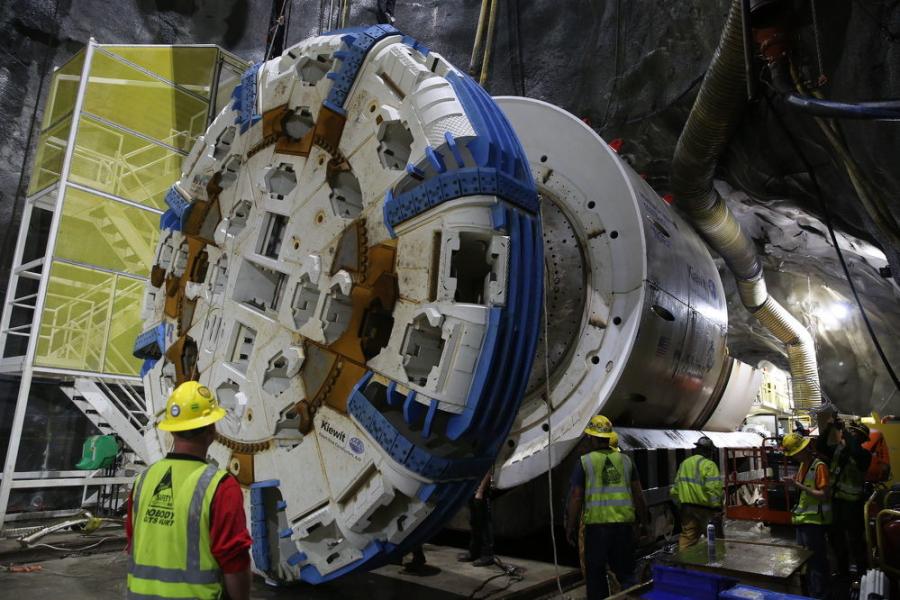

Bosch noted that the TBM is extremely large and impressive, weighing more than 2.7 million lbs. The machine had to be stored in almost two dozen pieces, taking workers months to assemble.

"You feel quite small when you stand next to it. It's 21.6 feet in diameter, 475 feet long when fully constructed. It's also unlike any TBM built in history, because it can withstand extreme pressures — about 8.5 times the amount of pressure in a typical car tire, or 11 times the amount of pressure that comes out of a garden hose."

"You feel quite small when you stand next to it. It's 21.6 feet in diameter, 475 feet long when fully constructed. It's also unlike any TBM built in history, because it can withstand extreme pressures — about 8.5 times the amount of pressure in a typical car tire, or 11 times the amount of pressure that comes out of a garden hose."

In September 2017, DEP officials appeared with federal, state and local representatives, guests and construction workers at a ceremony to kick off the project.

"The start of tunneling to repair the Delaware Aqueduct is a major milestone in the history of New York City's water supply system," DEP Acting Commissioner Vincent Sapienza told reporters. "While the city has added new facilities to its water supply over the past century, repairs approaching this magnitude have been few and far between. The effort to fix the Delaware Aqueduct is by far the most complex DEP has undertaken, and it highlights the absolute need to keep our public works in a state of good repair."

The advanced TBM was formally dedicated in honor of Nora Stanton Blatch Deforest Barney, a noted suffragist and the first woman in the country to earn a college degree in civil engineering. Nora, who worked as a draftsman on the city's first reservoir and aqueduct in the Catskill Mountains, also was the first female member of the American Society of Civil Engineers. She later became a developer and architect on Long Island and in Greenwich, Conn.

Placed into the chamber last year, the TBM has been driving the tunnel for several months, with approximately a third of the work finished. Assembly was overseen by a professional crew from Robbins, the company that built it. The TBM has many systems that need to function properly and talk to each other digitally, to make the machine work well. A lot of fine-tuning was needed before the TBM could start driving the tunnel and working its way up to the expected production rate of 50 ft. per day.

"We are working 24 hours, six days a week, so it's definitely not your typical job," said Bosch. "Most of these men and women are 800 to 600 feet underground for eight hours a day."

"We are working 24 hours, six days a week, so it's definitely not your typical job," said Bosch. "Most of these men and women are 800 to 600 feet underground for eight hours a day."

A key phase of construction for the bypass tunnel began as crews in Newburgh started lowering the $30 million TBM into a subsurface chamber located 845 ft. below the ground. Attention to detail has been critical during all phases of the repair project.

Of the two leaks, the larger is located along the western bank of the Hudson River in Newburgh. The TBM is necessary to build a 14-ft. diameter bypass tunnel alongside this section of the aqueduct. The 2.5-mile bypass is being constructed 600 ft. below the Hudson River, from Newburgh to Wappinger. Once finished, it will be connected to structurally sound portions of the existing Delaware Aqueduct to convey water around the leaking section. The leaking stretch will be plugged and permanently taken out of service.

Early on, workers blasted 130 linear ft. of "starter tunnel" in the direction the TBM is working. The starter tunnel makes room for the TBM, and gets it pointed in the right direction.

The new tunnel driven by the TBM involves more than 100 workers at the site. The TBM is equipped with dewatering equipment to pump 2,500 gal. per minute away from the tunnel as the machine pushes forward. The machine is outfitted with equipment to install and grout the concrete lining of the tunnel, and to convey pulverized rock to a system of railroad cars that follow the TBM as it works. The railroad cars travel back and forth between the TBM and the bottom of Shaft 5B in Newburgh, delivering workers, equipment and rock between the two locations. Tunneling is expected to take 20 months, from start to finish.

The finished bypass tunnel will be reinforced by 9,200 linear ft. of steel and a second layer of concrete after the TBM is finished driving its path beneath the river. Once those are in place, DEP will shut down the Delaware Aqueduct to connect the bypass tunnel to the existing aqueduct. The closure is planned for October 2022. The project is expected to be finished in 2023.

The finished bypass tunnel will be reinforced by 9,200 linear ft. of steel and a second layer of concrete after the TBM is finished driving its path beneath the river. Once those are in place, DEP will shut down the Delaware Aqueduct to connect the bypass tunnel to the existing aqueduct. The closure is planned for October 2022. The project is expected to be finished in 2023.

DEP has monitored the two portions of the aqueduct with leaks — one in the Orange County town of Newburgh, and the other in the Ulster County town of Wawarsing — since the 1990s. The leaks release an estimated 20 million gal. per day, about 95 percent of that escaping the tunnel through the leak in Newburgh. DEP has continuously tested and monitored the leaks by using dye, backflow, and hydrostatic tests, and hourly flow monitors provide near real-time data on the location and volume of the leaks.

Over the course of more than a decade, DEP used a cutting-edge, self-propelled submarine-shaped vehicle built in partnership with engineers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts to conduct a detailed survey of the entire 45-mi. length of tunnel between Rondout Reservoir and West Branch Reservoir. The contraption took 360-degree photographs while gathering sonar, velocity and pressure data to assist in determining the location, size and characteristics of the leaks. All the data gathered indicates the rate of water leaking from the tunnel has remained constant and the cracks have not worsened since DEP began monitoring them in the early 1990s.

In 2010, the city announced plans to address the leaks by building the bypass tunnel around the portion of the aqueduct in Newburgh. The project began with the excavation of two vertical shafts in Newburgh and Wappinger to gain access to the subsurface. Workers completed an underground chamber at the bottom of the Newburgh shaft. The chamber, roughly 40 ft. high, 40 ft. wide and 100 ft. long, was created to serve as a staging area for the TBM and the spot from which excavated rock could be brought to the surface by a large crane.

The existing Delaware Aqueduct will stay in service while the bypass tunnel is under construction. Once the bypass tunnel is nearly complete and water supply augmentation and conservation measures are in place, the current tunnel will be taken out of service and excavation will begin to connect the bypass tunnel to structurally sound portions of the existing aqueduct. While the Delaware Aqueduct is shut down, work crews also will enter the aqueduct in Wawarsing to seal the small leaks there.

The existing Delaware Aqueduct will stay in service while the bypass tunnel is under construction. Once the bypass tunnel is nearly complete and water supply augmentation and conservation measures are in place, the current tunnel will be taken out of service and excavation will begin to connect the bypass tunnel to structurally sound portions of the existing aqueduct. While the Delaware Aqueduct is shut down, work crews also will enter the aqueduct in Wawarsing to seal the small leaks there.

This is actually the first time the Delaware Aqueduct will be drained in 60 years. In 2013, DEP installed new pumps inside a shaft at the lowest point of the Delaware Aqueduct to dewater the existing tunnel before it is connected to the new bypass tunnel. The pumps will be tested several times before the tunnel is drained in 2022. The nine pumps are capable of removing a maximum of 80 million gal. of water a day from the tunnel, more than four times the capacity of the pumps they replaced from the 1940s. The largest of the pumps are three vertical turbine pumps that each measure 23 ft. tall and weigh nine tons.

The bypass tunnel project is expected to create nearly 200 jobs over eight years, with the vast majority of those jobs filled by local workers. Completely funded by the water rate payers in the city of New York, the undertaking has required an immense amount of cooperation between New York City DEP and other local offices.

"Remember that we are building it outside New York City, so it also takes coordination with the local communities and elected leaders in the towns where we are working," said Bosch. "It took dozens of permits from various regulators. A project like this one does not happen easily, so it takes everyone focusing and pushing in the same direction to repair the world's longest tunnel."

CEG

Today's top stories

"New York City's water comes from three reservoir systems — the Croton, Catskill and Delaware. When this leak was first discovered about 1990, there was not sufficient capacity in the other two systems, Croton and Catskill, to sustain the city during a shutdown of the Delaware Aqueduct. Since then, the city has implemented a number of programs including advanced metering in our distribution system, toilet replacements, etc., to drive down the consumption of water in the five boroughs."

"New York City's water comes from three reservoir systems — the Croton, Catskill and Delaware. When this leak was first discovered about 1990, there was not sufficient capacity in the other two systems, Croton and Catskill, to sustain the city during a shutdown of the Delaware Aqueduct. Since then, the city has implemented a number of programs including advanced metering in our distribution system, toilet replacements, etc., to drive down the consumption of water in the five boroughs." "You feel quite small when you stand next to it. It's 21.6 feet in diameter, 475 feet long when fully constructed. It's also unlike any TBM built in history, because it can withstand extreme pressures — about 8.5 times the amount of pressure in a typical car tire, or 11 times the amount of pressure that comes out of a garden hose."

"You feel quite small when you stand next to it. It's 21.6 feet in diameter, 475 feet long when fully constructed. It's also unlike any TBM built in history, because it can withstand extreme pressures — about 8.5 times the amount of pressure in a typical car tire, or 11 times the amount of pressure that comes out of a garden hose." "We are working 24 hours, six days a week, so it's definitely not your typical job," said Bosch. "Most of these men and women are 800 to 600 feet underground for eight hours a day."

"We are working 24 hours, six days a week, so it's definitely not your typical job," said Bosch. "Most of these men and women are 800 to 600 feet underground for eight hours a day." The finished bypass tunnel will be reinforced by 9,200 linear ft. of steel and a second layer of concrete after the TBM is finished driving its path beneath the river. Once those are in place, DEP will shut down the Delaware Aqueduct to connect the bypass tunnel to the existing aqueduct. The closure is planned for October 2022. The project is expected to be finished in 2023.

The finished bypass tunnel will be reinforced by 9,200 linear ft. of steel and a second layer of concrete after the TBM is finished driving its path beneath the river. Once those are in place, DEP will shut down the Delaware Aqueduct to connect the bypass tunnel to the existing aqueduct. The closure is planned for October 2022. The project is expected to be finished in 2023. The existing Delaware Aqueduct will stay in service while the bypass tunnel is under construction. Once the bypass tunnel is nearly complete and water supply augmentation and conservation measures are in place, the current tunnel will be taken out of service and excavation will begin to connect the bypass tunnel to structurally sound portions of the existing aqueduct. While the Delaware Aqueduct is shut down, work crews also will enter the aqueduct in Wawarsing to seal the small leaks there.

The existing Delaware Aqueduct will stay in service while the bypass tunnel is under construction. Once the bypass tunnel is nearly complete and water supply augmentation and conservation measures are in place, the current tunnel will be taken out of service and excavation will begin to connect the bypass tunnel to structurally sound portions of the existing aqueduct. While the Delaware Aqueduct is shut down, work crews also will enter the aqueduct in Wawarsing to seal the small leaks there.